iSixSigma.com published two excerpts from Creating a Kaizen Culture. Here a team in a Fabrication Department at Hill-Rom Industries learns about continuous process improvement from Shigeo Shingo. A second excerpt looks at engaging middle management in a culture of change at Bosch.

In July 1985, Mike Wroblewski was still a junior industrial engineers in the Fabrication Department of Hill-Rom Industries. The company had invited Shigeo Shingo, a consultant to Toyota and author of 10 books on industrial engineering, Kaizen, and the Toyota Production System, to teach the single minute exchange-of-dies (SMED) system. After Shingo met with the management team, Wroblewski, a setup operator and a tool-room technician, was selected to work with Shingo for one week to understand how the SMED system worked. Wroblewski did not know who Shingo was at the time. Shingo explained through an interpreter that we should be able to exchange our dies in 10 minutes or less. Working in the Fabrication Department, Wroblewski knew that the setups and die changes took between one and four hours on the presses that ranged from 75 to 400 tons. He could not conceive how this could be done in less than 10 minutes.

The Kaizen team watched and videotaped a typical die change, which took an hour. Shingo explained the difference between internal time and external time, asking, “What things can we do while the press is still running the previous job to have things prepared ahead of time?” He wanted the team to move activities that were internal to the downtime to be down external to the downtime – while the machine was still running – in order to reduce the die change time. The team followed this guidance and changed its method, resulting in a die change that was cut to 30 minutes. “We thought that was great, the best ever,” recalls Wroblewski.

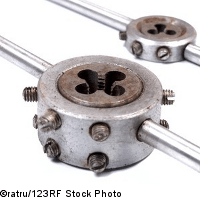

But Shingo was not satisfied. “Please try again,” he said, asking that the team look at standardizationsand adjustments. The team noted that the die heights were all different, took measurements, and made the die heights and pass lines the same. As a result, the 30-minute changeover time was cut to 20 minutes. Team members were delighted. But still, no celebration. “Please try again,” said Shingo, and this time he asked the team to look at bolts and clamping, which they were able to reduce from 18 different bolts to a few slotted attachments. As the team practiced the changeover, dies going in and out, team members improved little things each time across the week. The final result was that a changeover that took over an hour on Monday was performed in less than 5 minutes on Friday. The team had beaten the 10-minute mark.

“Shingo made us feel that we did it ourselves and he just pointed the way. It was the greatest feeling in the world to us to accomplish what was thought to be impossible. My world of possibility and improvement became endless,” said Wroblewski. Indeed, during the week, the team made the emotional journey from shock and denial (“It’s not possible”) to acceptance (“Maybe we can do it”) to a feeling of pride at achievement. Thus it was a surprise at the end of the presentation of results when Shingo said, “Please try again.” He gave further hints on how the team could still save 5 seconds here, 10 seconds there. The message sunk in: Continuous improvement truly is continuous, and there is always something more to improve.

“What we learned that day,” says Wroblewski, “is that although all week we thought the 10-minute mark was the goal, it was only the direction.”

Wroblewski and the team members experienced many emotions, no doubt positive and negative, during their Kaizen event with Shingo. Also, it is clear that there were times when they were confused about what was possible, what they must do, and finally, what the long-term goal of the SMED exercise really was. This confusion was resolved by the very end, resulting in an “A-ha!” moment for them.

A study by D’Mello and Graesser suggests that negative emotions and “productive confusion” can help students to learn more effectively in complex learning situations. Participants in the study reported being in neutral emotional states about a quarter of the time while feeling surprise, delight, engagement, confusion, boredom, and frustration during three-quarters of the time. D’Mello and Graesser found that learners move back and forth between states of “engagement/flow” and “cognitive disequilibrium” as they are faced with obstacles or contradictions and they are able to resolve them through thought, reflection, and problem solving. The uneasy feeling of being mentally thrown off-balance motivates us to find the answer, and learning occurs.

This is significant for people going through Kaizen transformations because they will be faced with many counterintuitive experiences while practicing Kaizen. These ideas include the fact that the vast majority of the work we do does not add value, that less inventory is often better, that one-piece flow is more productive than batching, that checking at every step costs less than checking quality once at the end, that it is better to stop work when a problem is found than to keep working, that taking time each morning to meet as a team results in better performance than saving that time and using it to start work early, that the smallest changes can have big impacts, and so forth. The mindful Kaizen facilitator can even use emotions such as confusion to the advantage of the learning process.

Reference

D’Mello, Sidney, and Graesser, Art (2012). “Dynamics of affective states during complex learning.” Learning and Instruction 22(2).