Fifteen years ago, a student of mine introduced me to the Toyota Way. As a participant in a project management program and then in a Six Sigma course, this young man (who happened to be across the world from me in Japan) began posting assignments using methodologies from his employer, Toyota.

Fifteen years ago, a student of mine introduced me to the Toyota Way. As a participant in a project management program and then in a Six Sigma course, this young man (who happened to be across the world from me in Japan) began posting assignments using methodologies from his employer, Toyota.

Later, that student became my teacher, or sensei, and I began to learn about Lean and how to implement it the right way. I had learned about Lean before, but I discovered that in North America Lean was often not applied properly; much of what was important in the methodology had been lost in translation.

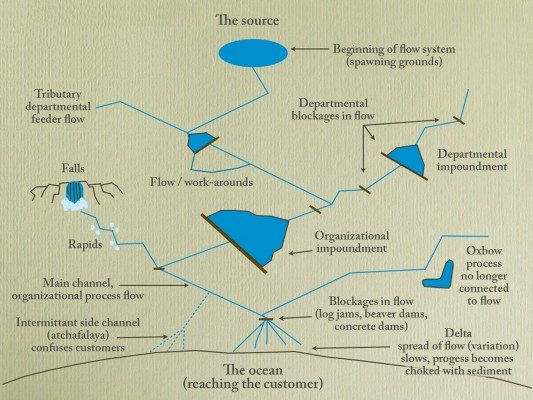

My sensei explained to me that organizational flow was like a river that had many branches. It runs downstream from its source until it reaches the ocean. As with an actual river, there are blockages that hold up the flow. Some blockages are naturally occurring log jams, while some are created by busy beavers. Still others are inadvertently placed in the middle of the flow due to poor organizational policies or other management issues. Sometimes the pressure behind the blockage becomes so great that the flow circumvents the blockage becoming a work-around that can take far longer than the original stream.

Breaking Through the Blockages

The smaller blockages can be seen as opportunities for kaizen, or “change-good”; in North America, these are chances for incremental process improvement. The larger blockages can be seen as opportunities for kaikaku, or “change-great.” This is the idea of transformational process improvement rather than small incremental change. (My sensei introduced me to this concept and I found it nowhere else in the Lean body of knowledge.)

Opportunities for both kaizen and kaikaku can be found anywhere in the flow of either the main channel or the departmental tributaries.

Department Tributaries

Departments in the organization are feeder streams to the main flow of the water, but they may have blockages along them. Some of the blockages can reach the magnitude of impoundments restricting most of the flow of the water. These blockages may result from processes directed by the department manager who wishes to personally check the quality of the output of their department, but who does not have the time to accomplish such a daunting task. Thus, little flow trickles out from the department.

Other departments contain rapids and waterfalls that can destroy product or services that are supposed to be provided. Although the flow is not significantly restricted, the output is chaotic.

Some departments look unrestricted in their flow but upon closer examination it is clear that there are oxbows of processes that are superfluous – they consume resources and hold unutilized potential.

As the flow gets closer to the ocean there may be intermittent side channels that run to the sea causing confusion on the part of the customer who then does not know where or when to receive the product or service.

Finally the output reaches the delta, but the diverging flow into multiple channels slows down the progression and the channels themselves become overgrown and choked with sediment, not to mention toxic due to the loss of oxygen. Few channels remain properly connected to the ocean and reach the customer in the form and function they were originally designed to accomplish.

| The Steps of the River | |

| Step | Description |

| Source | Where the processes of the organization begin |

| Blockages in flow (log jams, beaver dams, concrete dams) | Anything that gets in the way of flow throughout an organization |

| Departmental blockages in flow | Anything that gets in the way of flow in a department |

| Department impoundment | Large blockage creating extensive process backups in a department |

| Flow/workarounds | Flow backs up to the point where it runs around the blockage and a new channel is created |

| Organizational impoundment | A severe blockage in the main flow of organizational processes |

| Falls and rapids | Chaotic flow – while fast, may cause damage to people and property |

| Main channel organizational process flow | Where all of the flow comes together and mixes into organizational output |

| Intermittent side channel | When flow becomes too heavy for the main channel to hold, it seeks another channel |

| Oxbow | A previously-used channel that has been cut off from the flow |

| Delta | Multiple channels of final flow to the customer |

| Ocean | The vast area of potential customers |

The Pull of Gravity

Gravity, or customer demand, is the most powerful form of pull in an organization. Those in leadership positions have a great desire for the number of blockages to be reduced or eliminated – especially those blockages that cause the greatest amount of flow restriction and interact with that gravitational pull of the customer.

Leaders hire external consultants who seem knowledgeable about river systems to identify and remove the largest of the obstructions, but those leaders often do not think about what will happen to the rest of the organization downstream. Flooding will occur, side channels will be carved and assets will be washed away; human and material costs can be severe.

What can be worse is that some consultants think they must start at the beginning of the flow and work their way down to the ocean, removing blockages as they go. They end up disrupting the entire system. The cost of this approach is staggering! But these are the two most used approaches in quality management improvement in North America: 1) target the biggest blockages and 2) start at the beginning.

A Better Approach

My sensei taught me that the first thing to do is analyze the system and determine the locations of, and the reasons for, the blockages. Then map the blockages while identifying the sections that provide value (value steam mapping).

Once that mapping is accomplished, a team must work its way up from the ocean, eliminating blockages as it goes until the entire system has free flow (using 5S, training-within-industry standard work, takt time and cycle time).

Then and only then can a team go back and begin projects, utilizing proper project management principles, to remove or reduce falls and rapids, end work-arounds, reconnect or drain oxbows (that is, reduce waste), and finally – through the reduction in variation – dredge out one clear channel to the customer.